The Billion-Dollar Giveaway

How IBM grew a market by opening their architecture, and why AI just did the same thing

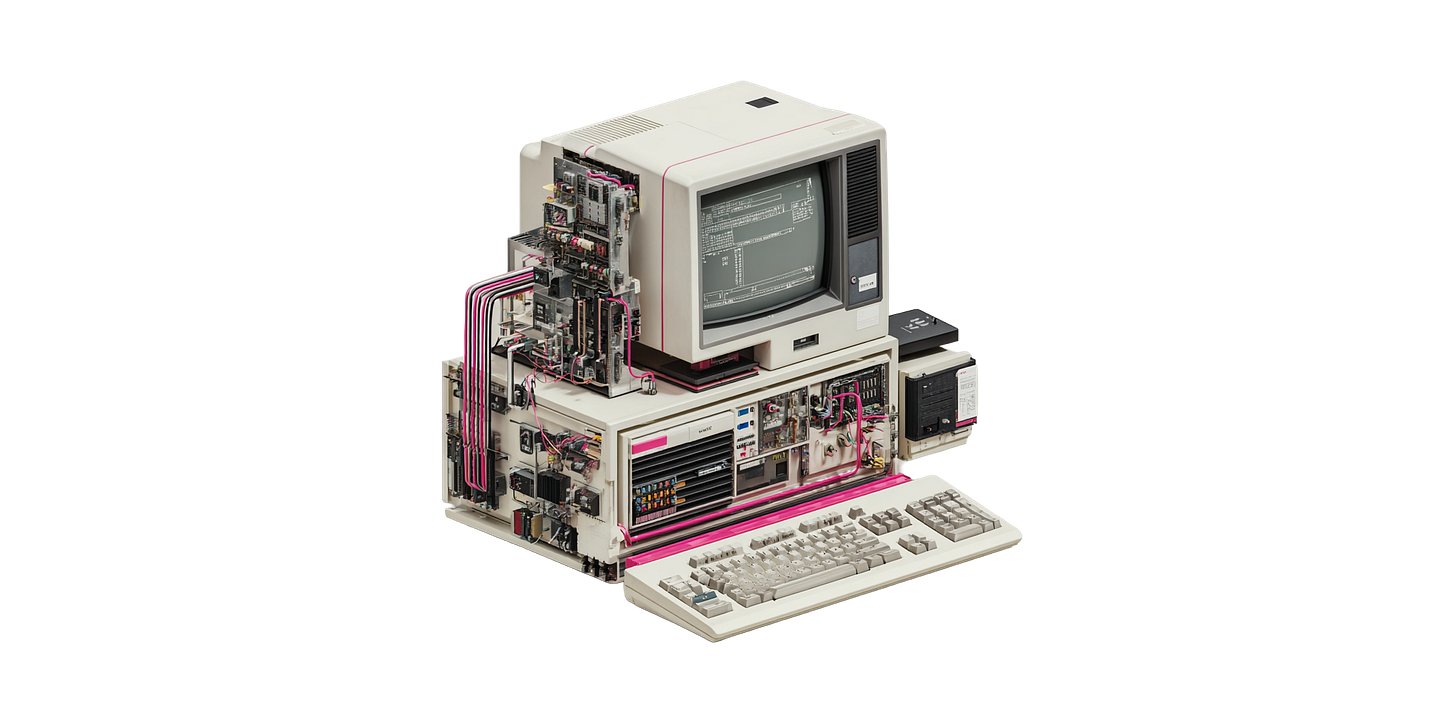

I remember the first time I got my hands on a PC. It was around 1985, maybe a year or two earlier. We called it an “IBM,” even though I am pretty sure that one didn’t have an IBM logo on the box. It had an Intel 8086 or 8088 processor inside: an “IBM PC XT”. The amber characters glowing on the black screen were mesmerising. I sat in front of it. I didn’t do much beyond typing a few random characters and hitting Enter. It was a family visit, and I was a small kid who could barely read. When my parents spotted me playing with the machine, I was promptly moved away from it. Too late. I was hooked. Forty years later, I still am. Clearly, a core memory had formed.

Opening up to grow a market

That machine was likely a Taiwanese clone built by some small business, owned by someone who’d never worked for IBM, sold by someone who’d never met anyone from IBM, running software that IBM didn’t write1.

Yet it was exactly what IBM was trying to achieve.

A few years earlier, in August 1981, IBM did something that looked completely insane: it published the complete technical specifications for the IBM PC. Circuit diagrams, interface specifications, every detail a competitor would need to build an exact copy. Why did they do it? Because they believed they weren’t large enough to develop all the hardware and software to make the personal computer a truly global success.

In its first year, IBM’s PC generated $1 billion in revenue. By 1984, that had grown to $4 billion, even as clones flooded the market and IBM’s market share shrank. The open architecture drove market growth so fast that IBM’s revenue quadrupled, and competitors thrived as well.

The pattern repeats. Google gave away Android for it to dominate mobile. The Internet itself emerged from the open TCP/IP protocol, and later HTTP and HTTPS. USB, Bluetooth, and WiFi - all open standards that pushed out proprietary alternatives and grew markets by billions2.

In all these examples, someone realised that controlling the standard was less valuable than growing the market. They traded exclusivity for ubiquity, and commoditised their advantage to grow the pie.

Earlier this month, the AI industry made a similar move. And like in 1981, most people missed it.

First, The Standard Gets Built

In November 2024, Anthropic, the makers of Claude, released MCP, or “model context protocol”. Apart from software developers, almost nobody noticed. I’ve been talking about MCP at my keynotes since early 2025. Here’s me earlier this year opening the Masters and Robots conference in Poland.

MCP is a standard way for AI models to talk to external systems: databases, online stores, design tools, anything on the web. Before MCP, connecting an LLM to real-world systems meant custom integration work for every model-system combination. With MCP, you teach the model the protocol once, and it can talk to anything else that speaks MCP.

Think of it like this: MCP is to AI agents what HTTP is to web browsers. A standard way to access resources on the Internet.

The impact came fast. Within months, thousands of implementations appeared. Grasshopper Bank built an MCP server so customers could check balances by talking to Claude. Figma added one for AI-assisted design. Today, mcpmarket.com lists over 18,000 MCP servers.

But a protocol only works if everyone adopts it. And proprietary protocols rarely get universal adoption. This is why Android phones can’t see iMessage effects: Apple controls the protocol.

Anthropic released MCP as an open specification. Anyone could implement it.

But there’s a difference between ‘open’ and ‘neutral.’ The specification was open: anyone could read it and implement it. But Anthropic still controlled the protocol’s evolution. They decided what features got added, how they changed, and where they went next.

For Google, Microsoft, and OpenAI, companies competing with Anthropic for AI dominance, that’s a problem. Would you build your entire agent infrastructure on a protocol your competitor controls? Would you invest billions in an ecosystem where your rival makes the rules?

Open specifications get adoption. Neutral standards get universal adoption.

And, pulling an IBM move, Anthropic made MCP truly neutral. They gave it away.

Then, It Gets Opened For Real

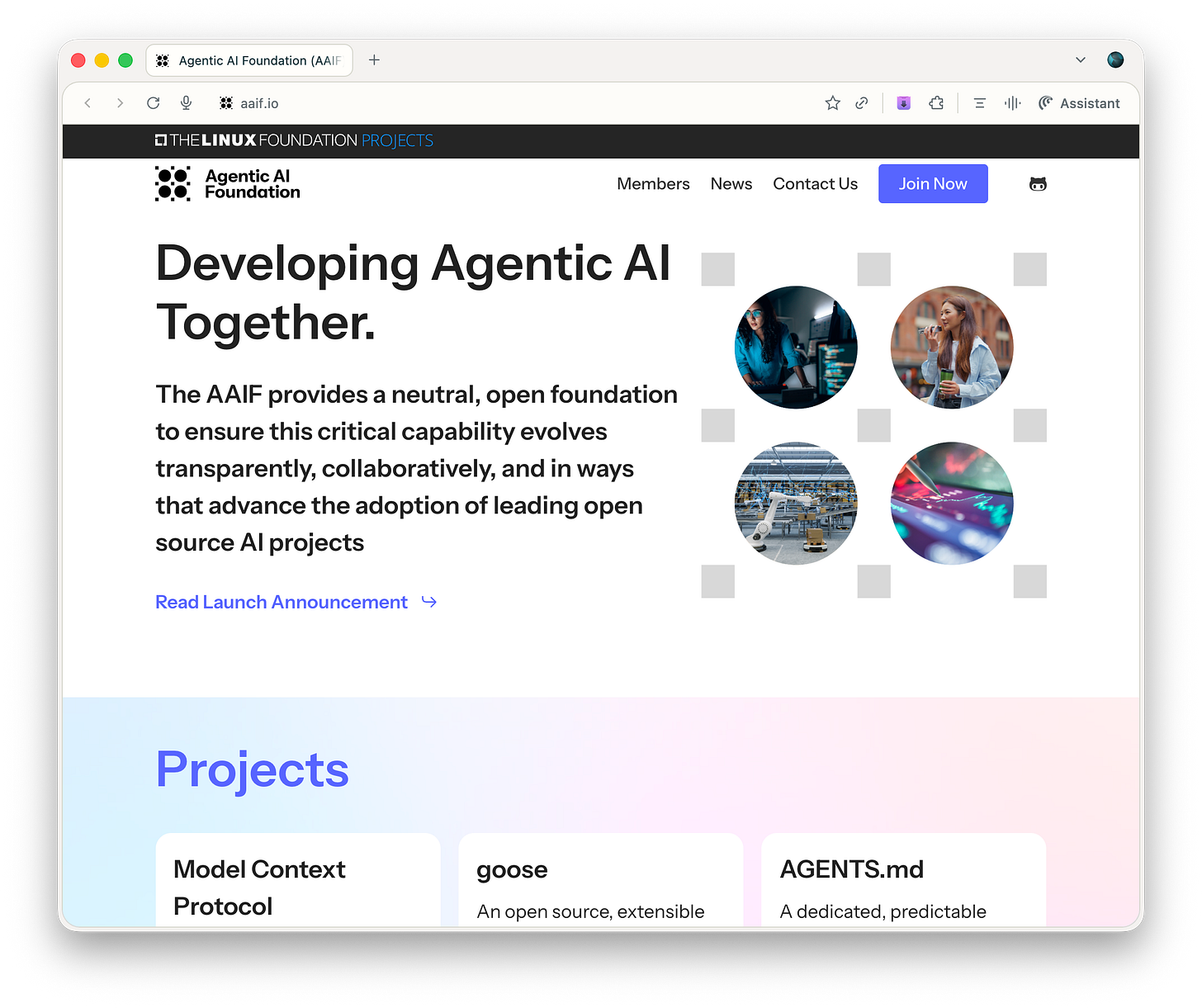

On December 9, 2025, the Linux Foundation announced a new initiative: the Agentic AI Foundation (AAIF). Anthropic donated MCP to the new foundation, joining two other projects: goose (Block’s AI agent framework) and AGENTS.md (OpenAI’s project-guidance standard).

The Linux Foundation provides neutral project governance. When a company donates technology to the Linux Foundation, they surrender control. The protocol’s evolution is governed by community consensus. It’s the same model that made Linux, Kubernetes, and Node.js into universal infrastructure (if these names don’t ring a bell, you’ll have to trust me here: these are some of the more important building blocks of the Internet).

The list of founding members is impressive: Amazon Web Services, Anthropic, Block, Bloomberg, Cloudflare, Google, Microsoft, and OpenAI, plus dozens more at gold and silver tiers. These are all competitors in an AI race.

Would Google build its agent infrastructure on a protocol controlled by Anthropic? Would Microsoft? The answer is already clear. But a protocol governed by the Linux Foundation, where no single company sets the agenda? “That changes everything”, as a Slopfluencer would say.

This is the same pattern as in 1981. Release the technology openly to prove it works. Then give up control to make it truly universal and grow the market.

So what?

Right now, it’s unthinkable for a retailer not to have a website. You’d be invisible to half your customers.

In eighteen months, it will be unthinkable not to have an MCP server. You’ll be invisible to every AI agent navigating the web on behalf of their users.

This is the B2A2C model from The Economy of Algorithms: Business-to-Agent-to-Consumer. The agents mediate the relationship. They compare your offerings against competitors. They negotiate on behalf of their users. They place orders, book appointments, and request quotes.

And if your systems can’t talk to agents? You don’t exist in their world.

Early adopters are making their businesses agent-accessible right now. They’re building MCP servers and making their data and services available through standardised protocols. Late adopters will spend 2027 paying consultants to retrofit systems that early adopters got right the first time.

Infrastructure moments don’t wait. TCP/IP in 1983. HTTP in 1991. Mobile-responsive websites in 2010. And now: agent-accessible interfaces in 2025.

That machine I touched in 1985? It might have been made by Multitech, a small Taiwanese clone maker capitalising on IBM’s open architecture. Today, Multitech is Acer: one of the world’s largest PC manufacturers. They exist because IBM gave away the blueprint.

There’s a possibility that one particular piece of software, so-called BIOS, in the machine, had been written by IBM, but I think it’s too technical for this newsletter - feel free to ask me to elaborate in comments, though.

Tesla tried this in 2014, opening their EV patents to grow the market. But competitors didn’t follow: they built their own tech. Turns out, opening your patents only works if people actually need what you’re offering and the terms are genuinely neutral.

IBM didn’t just give away architecture, it externalized coordination.

MCP feels similar: growth explodes, but decision rights and blame diffuse. That’s powerful infrastructure and a different kind of risk surface.