Almost every evening, when the house quiets down, my wife and I sit down in front of the TV.

Snacks in hand, we start browsing Netflix titles. We’re not taking this task lightly. I check IMDB and Rotten Tomatoes’ ratings for each show that catches our attention. In most cases, the ratings turn out to be super low. By the time I’ve cross-referenced the third Korean thriller against its Metacritic score and read four contradictory reviews about whether the ending is worth it, we’re basically living proof that infinite choice is a curse. And one of us (I won’t disclose who) is fast asleep. We end up leaving the TV on, playing some YouTube slop about tourists arguing to Australian border agents that dried slugs are not food.

Why do we even pay for Netflix?

Really. Think about that for a second.

We’ve already cancelled our Disney+ subscription. Too much to choose from.

Let that sink in.

We had two TV channels when I was growing up. We watched whatever was on. We were happy. Now I have five streaming apps, with thousands of shows each. And I don’t watch anything.

The Search Cost Crisis

My Netflix problem is noise disguised as choice. What I call Tuesday night, economists refer to as “search costs exceeding value.” The effort required to find something good has become more exhausting than just watching something bad.

This is, of course, not just media. Every Google search returns 10 million results. Every LinkedIn feed has infinite posts. Excel has hundreds of functions. Including WEBSERVICE, which can literally call the internet. And every consultant can offer an infinite number of strategies, generated fresh this morning by Claude.

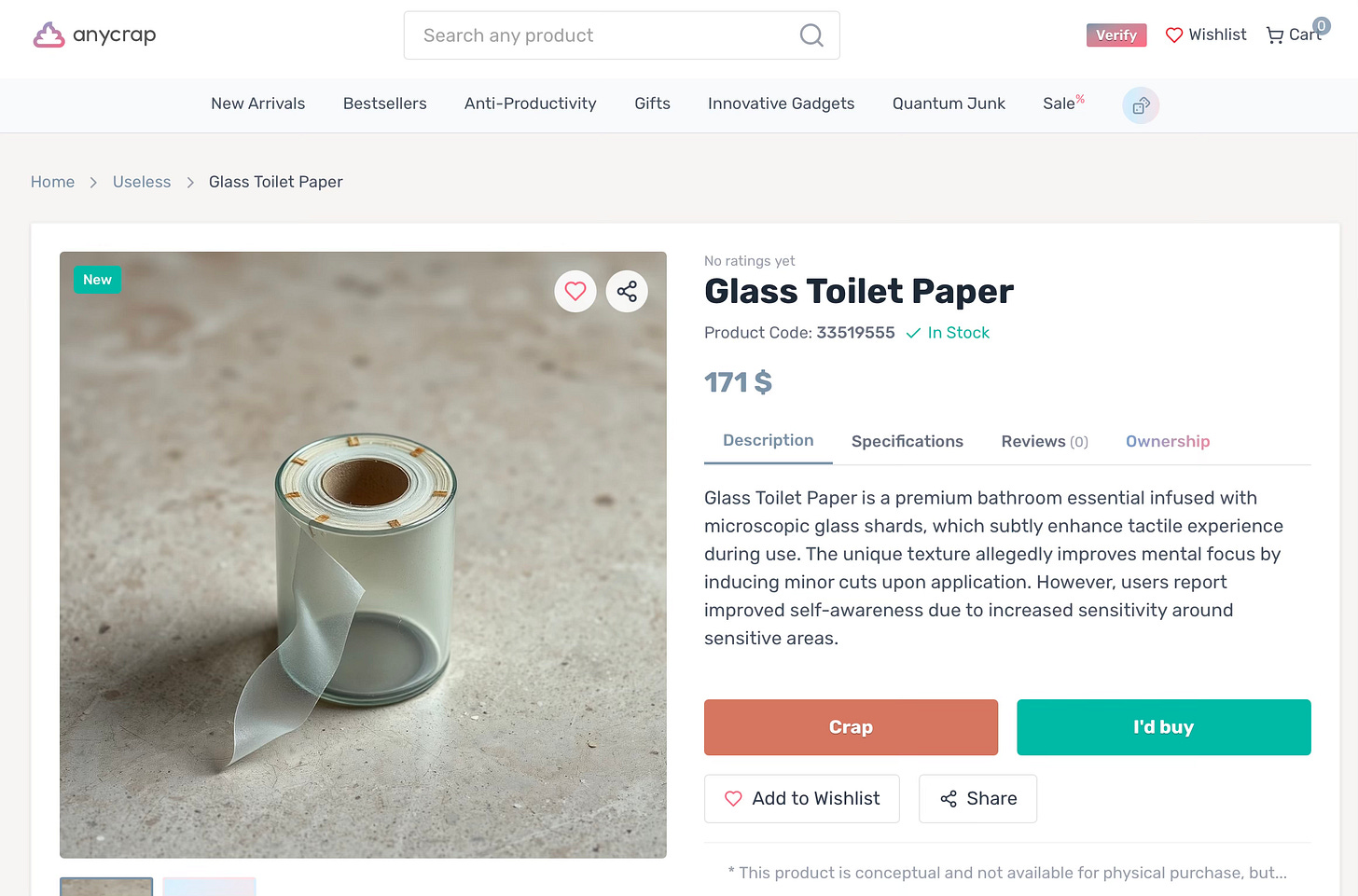

GenAI models can create 10,000 product variations in minutes. See for yourself: go to anycrap.shop and add a new product to their catalogue. I just suggested Glass Toilet Paper. The system created a beautiful product page, including an AI-generated description, stating that it “is a premium bathroom essential infused with microscopic glass shards, which subtly enhance tactile experience during use”. Please don’t judge me.

Every company now has access to infinite content generators, infinite feature creators, infinite everything-makers. The marginal cost of creation started diving towards zero the moment ChatGPT launched.

The human response? We’ve stopped looking.

My friends no longer search for restaurants. They go to the same three places. Some executives don’t read industry news. They rely on WhatsApp groups with six people they trust. Nobody discovers new music. We loop the same Spotify playlist from 2019.

The Silence Premium

In the land of infinite noise, silence becomes luxury.

Here are a few examples of businesses that seem to be going the opposite direction. Instead of adding to the noise, they remove it.

Costco charges $65 annually just to enter its stores. In return? Offering at most 4,000 products instead of the 40,000 at typical supermarkets. They raised membership fees from $60 to $65 in September 2024 and maintain a whopping 92.7% renewal rate. People pay for less choice.

The Economist doesn’t cover everything. It decides what matters this week and ignores the rest. They now have 1.25 million paid subscribers, with two-thirds of revenue from subscriptions. In a world of infinite news, they sell finite curation.

In-N-Out Burger has had essentially the same menu since 1948. No breakfast. No chicken. No salads. Just burgers, fries, and shakes. McDonald’s tests 100+ items annually; In-N-Out does three things, nothing else. Revenue: $2 billion a year.

Notice the pattern? These companies are cancelling noise.

And they’re not alone. The entire economy is reorganising around three principles that would have gotten you fired in 1995:

Scarcity as Strategy, or Less Is More: Supreme drops limited items on Thursdays at 11 am. Small batches, no restocks. Zara launches hundreds of new items every week, but it’s Supreme that has people camping outside at 3 am. I know, because my son once made me wait in one of these lines.

Curation as a Service, or Quality over Quantity: Wirecutter tests 100 toasters to recommend one. That’s it. One. Their business model? Saving you from reading 100 Amazon reviews written by bots and sociopaths.

Constraint as Value, or Stay in Your Lane: When Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, he drew a 2x2 grid: Desktop/Laptop, Consumer/Pro. Four products. Down from dozens. The board thought he was insane. Yes, they’ve expanded since - watches, phones, earbuds. But the principle remains: deliberate constraint. That discipline is worth close to $4 trillion.

AI handed everyone a content infinity machine. GPT, Claude, Midjourney - they made creation virtually free. Every competitor is racing to generate more, publish faster, and deliver an infinite number of features. It feels insane not to use these tools to produce everything possible.

But perhaps that’s exactly why you shouldn’t.

Your Noise Audit

Three questions to discover if you’re drowning your customers.

Scarcity Check: Would removing this make your customers’ lives simpler?

Which emails would they pay you NOT to send?

Which features would they celebrate if you deleted?

Which products would they thank you for discontinuing?

Curation Check: Are you asking your customers to do work that you should be doing?

Where are they drowning in your options?

What decisions are exhausting them?

Where could you choose FOR them?

Constraint Check: Does saying no make you more valuable to your customers?

What is everyone in your industry doing that you shouldn’t?

Where would saying “no” become your differentiator?

What expansion would dilute your value?

Remember my Netflix ritual? Forty-five minutes of browsing, cross-referencing reviews, and one of us falls asleep while the other is still scrolling. We’ve spent more time choosing than we would have spent watching. What if that’s your product? What if that’s your service? What if that’s what you’ve become?

Excellent points Marek and I'll be using the key questions in a forthcoming PL hub development