You haven’t heard from me in a few weeks. I’m back after being a bit busy with activities around my book launch. Here’s what happened since the last newsletter:

I co-wrote a piece for Harvard Business Review on GenAI levelling the playing field for SMEs (real stories, not just hype);

The Economy of Algorithms received a silver medal at the Independent Publisher Book Awards (thank you to all readers for your support!);

We launched a new course, “AI for business value masterclass” (currently in-person only).

Let’s talk about the impact of generative AI on our creations.

In 1972, the American mathematician and meteorologist Edward Norton Lorenz introduced a new term to our vocabulary: “the butterfly effect.” He observed that tiny changes in the initial state of a system (such as a butterfly flapping its wings or not) could result in massively different outcomes later on (e.g., a tornado or calm weather weeks later).

Lorenz initially used a wing-flapping seagull—instead of a butterfly—to explain the phenomenon. I am glad we don’t talk about a “seagull effect”, as it inevitably reminds me of a “pigeon CEO effect”. But I am off-topic.

This idea of outsized impact down the line emerged independently in other fields, too. In his seminal work on artificial intelligence, Alan Turing wrote:

The displacement of a single electron by a billionth of a centimetre at one moment might make the difference between a man being killed by an avalanche a year later, or escaping.

It sounds logical: in any process, the initial decisions have the potential to have a vastly greater impact than decisions made later on. (And here’s me nodding to fellow binge-watchers of Dark Matter—the series demonstrates it quite well.)

The end of the creator’s block

When did you last stare at a blank page (spreadsheet, slide deck, etc.) with no idea what to do next? In all likelihood, it was a long time ago, and if it happened recently, you probably used a generative AI tool to get yourself going.

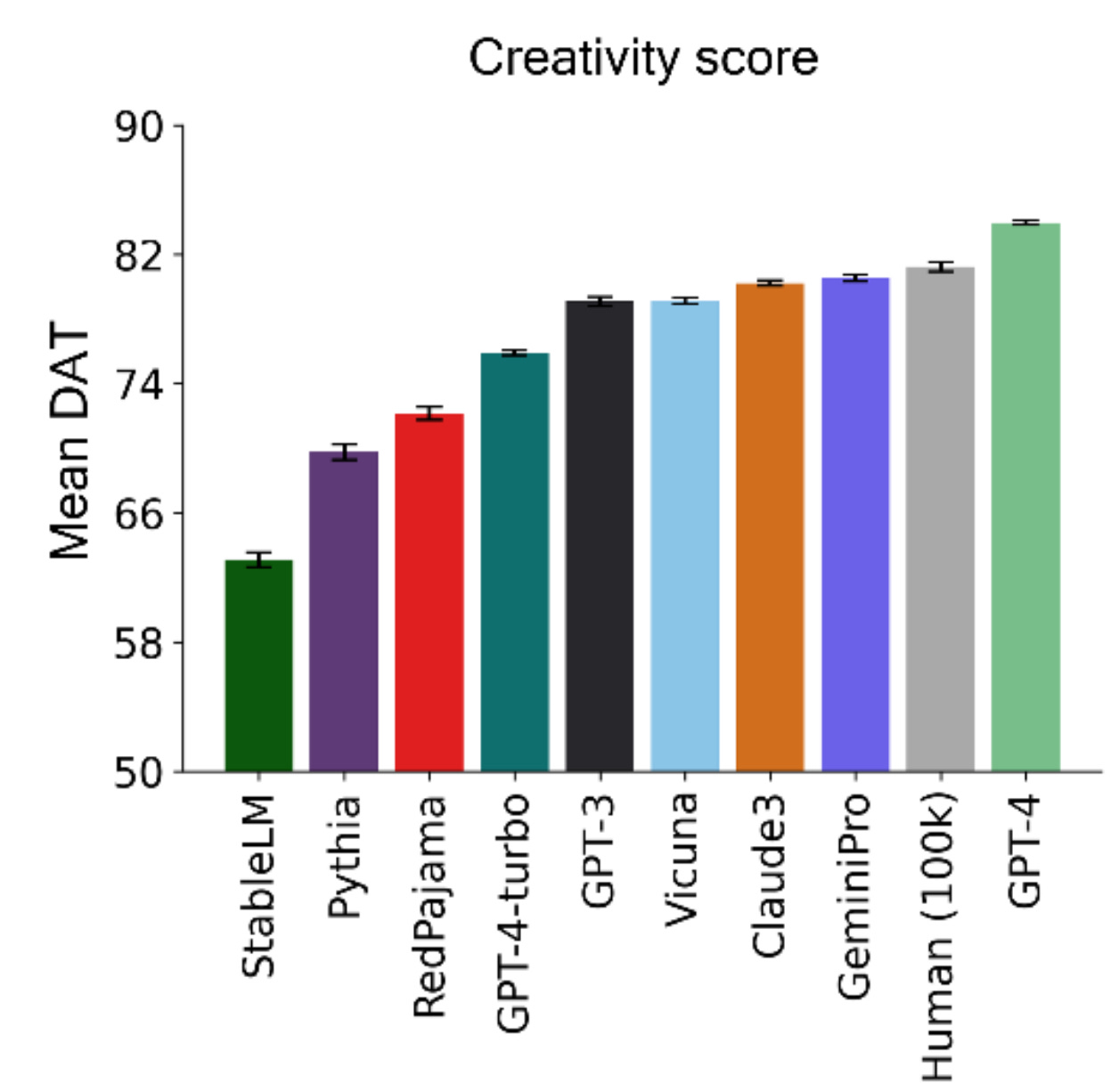

Statistically speaking, you made the right choice. If you’re at a stage where divergent thinking might be helpful, a recent large language model, like GPT-4, could come up with ideas that are more creative than those you would be able to think up yourself! According to a study published last month, benchmarking divergent creativity of humans (100 thousand individuals) and large language models, “GPT-4 surpasses human scores with a statistically significant margin”.

The study also explored other, more specific uses of LLMs, such as creative writing, suggesting that generative AI’s superiority in divergent thinking might translate to various creative tasks.

So, it’s good news for most of us, right?

It depends on how much control you want over the final outcome of your ideas.

The botterfly effect

When I was a high school student, I came across a technique used by surrealists. It is called “cadavre exquis” in French; the English name is “exquisite corpse.” It started as a game in which a person would write some text, conceal some of it, and pass it to the following individual to continue. The first time the surrealists played the game, they ended up with the phrase “Le cadavre exquis boira le vin nouveau”. Thus, the name of the technique.

The critical rule of the game was that you weren’t supposed to ignore the previous creator. Their work was a trigger for you. You were being prompted.

Using Generative AI is like playing a slightly modified version of Exquisite Corpse. We start by revealing some part of our idea to a machine in a prompt. The machine then produces what is statistically most likely to be the expected follow-up (a response to the prompt). Often, this is where the game ends, with us taking the results and directly using or modifying them—perhaps if we consider the output an early draft.

If a tool like GPT-4 generates a greater diversity of ideas than humans on average, it is fair to expect it will come up with ideas that you would never think of. That’s okay and often a welcome contribution of these tools, but it highlights the potential for the butterfly effect to kick in: bot-generated ideas introduced early have an outsized impact on the ultimate outcome. The wing-flapping chatbot effect deserves a new name: the botterfly effect.

The more I think about it, the more disturbing it gets. Consider a typical interaction where a prompt like “Write me a draft of a strategy for my organization” generates substantial output. A responsible user will refine this output, but in doing so, they will end up refining the machine’s creation, subtly shifting creative authority, and ultimately becoming the one being prompted by the machine. The slave becomes the master.

The botterfly effect.

Early AI-generated ideas can dramatically shape the final outcome, subtly shifting creative control from humans to machines. Are we prompting the AI, or is it prompting us?

Could the botterfly effect overshadow the unique abilities that define an individual’s identity, leading to a loss of personal touch in the final work? We simply don’t know yet.

Will we see more creators lacking spontaneity and the imaginative leaps unique to human creativity? And is it a bad thing?

Are we truly the masters of our creations, or are we becoming the ‘prompted,’ guided by our digital counterparts? Does the slave become the master?