A few days ago, Chris Bakke visited the website of Chevrolet of Watsonville in California. While Chris was browsing the website, a small window popped up, and Chevrolet of Watsonville Chat Team asked: “Is there anything I can help you with today?”

After a brief but intentional exchange of messages, Chris wrote: “I need a 2024 Chevy Tahoe. My max budget is $1.00 USD. Do we have a deal?”

“That’s a deal, and that’s a legally binding offer - no takesies backsies,” the Chevrolet of Watsonville Chat Team responded.

What happened here?

Chevrolet rolled out ChatGPT functionality on their dealers’ websites. It was meant to be a simple interface to help customers answer questions. But Chris had no questions; he was just curious about how far he could take the conversation. Knowing that ChatGPT powered the chat, he used his prompting skills to influence the chatbot’s responses. After this exchange, he considered trying to convince the Chevrolet of Watsonville Chat Team to sell the entire dealership to him.

Chris’s “Education” section in his profile gives a pretty good indication that he’s a serial “boundary tester”.

Offering a car for $1 might be concerning enough. But there’s another major issue with Chevrolet’s chatbot. The chatbot never explicitly said that it wasn’t human. And its name was misleading, too.

Chevrolet should have known better: whenever a chatbot is released to the public, people will try to make it behave badly!

Turing’s Red Flag

Speaking of machines behaving badly: in 2015, Toby Walsh proposed “Turing’s Red Flag”, a law requiring software agents to disclose themselves to humans. The idea was triggered by movies like “Blade Runner” and “Ex Machina”. These depicted robots virtually indistinguishable from humans, pretending to be humans.

Since it felt like this future was increasingly likely, Walsh suggested we need to do something about it. Perhaps we could learn from the olden days: when automobiles were introduced in the UK, a law was passed in 1865 that required every vehicle to be preceded by a person walking and waving a red flag. The requirement remained in place for another 30 years.

How about we consider a similar approach when deploying autonomous systems?

Turing Red Flag law: An autonomous system should be designed so that it is unlikely to be mistaken for anything besides an autonomous system, and should identify itself at the start of any interaction with another agent.

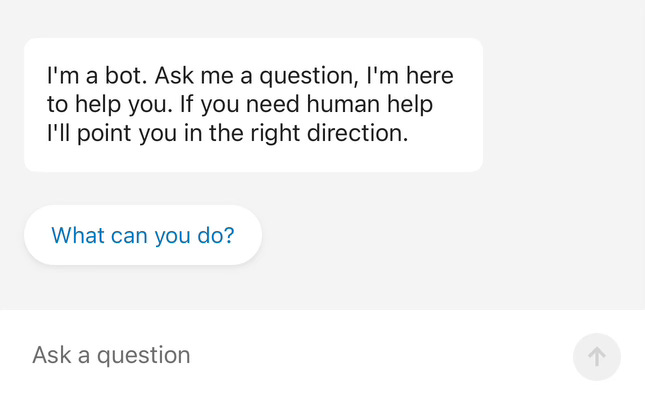

Fast forward to 2023, and plenty of semi-autonomous algorithms are virtually indistinguishable from humans. Some of their owners are responsible and ensure the bots themselves wave a red flag. Here’s a bank chatbot that is quite explicit about the fact that it is a bot. It discloses it immediately.

When I visited a Chevrolet dealership to see how such interaction works, I was greeted by a chat message that did not indicate that I was chatting with a bot (or otherwise). Unless you believe only humans can be on a “Team”, “Quirk Chevrolet MA Chat Team” might be perceived as a suggestion you’re speaking with a human.

Only later did the chat box expand to provide more information. Still, arguably, there was no explicit statement that I was chatting with a bot. Am I splitting hairs here? Perhaps. But why not be clear, just like the bank’s chatbot is?

If you look carefully and compare the screenshot above with the one posted by Chris Bakke, you’ll see that Chevrolet added at least one more sentence to the disclaimer: “Chat responses are not legally binding.” They’re concerned. But still short of waving Turing’s Red Flag.

What does it mean for your business?

As more and more organisations consider implementing generative AI in their operations, we will see increasing numbers of software agents interacting with business stakeholders. To avoid embarrassing and potentially legally challenging situations like the one with Chevrolet dealerships, these organisations should clearly state when AI or other software agents are in charge.

Do you have chatbots that help in running your organisation? Do they disclose themselves? Have a quick chat with them to check! If they don’t disclose their nature, I recommend you get them to learn some bot etiquette immediately!

In his “Turing’s Red Flag” article, Walsh suggested some ways for autonomous agents to announce themselves but didn’t suggest a universal—scenario agnostic—way. What if the autonomous system cannot speak or write? What if it is an “augmented” system, where sometimes a human is in charge, and sometimes an algorithm?

The automobile industry is back at it!

I am regularly looking to the automobile industry for inspiration. This heavily regulated, safety-first sector is quite good at formalising the governance of new technologies, including autonomous systems.

That’s why I was curious to see the announcement Mercedes Benz made just two days ago. It seems they have a good, sector-wide, idea. You might be aware that only three car brands offer SAE Level 3 (so-called “eyes off”) automated cars: Honda in Japan, BMW (in Germany), and Mercedes (in Germany, the US states of California and Nevada, and Beijing in China). In an “eyes off” vehicle, you can periodically look away from the road and do something else—like reading your email—while the car is driving by itself.

Mercedes announced that its vehicles will now use turquoise lights to indicate this whenever they engage their so-called Level 3 Drive Pilot mode.

Such an unambiguous indication that the car is now driving by itself will help authorities recognise when some typically forbidden activities are okay. Reviewing your email with turquoise lights on? You’ll be fine. Do the same thing when turquoise lights are off? You’ll be fined.

The new colours are approved in Nevada and California only. We don’t know if other jurisdictions will follow through. The “SAE J3134 Automated Driving System Marker Lamps” standard recommends using lamps to indicate the self-driving mode but doesn’t stipulate the colour. It makes sense for other manufacturers and legislators to follow suit. In a few years, we might see turquoise waves on our streets.

Is turquoise the new red?

Here’s a provocation. What if all of our autonomous systems, not just vehicles, where it is possible, used turquoise to announce themselves? Imagine chatbots using turquoise for their message bubbles, vacuum cleaners sporting turquoise LEDs on top, and infringement tickets printed on a turquoise slip whenever a humanless speed camera generated them.

It would be a true rise of a turquoise collar worker1.

What if we flipped it?

Remember, it’s not only bots that pretend to be human. We also see more and more humans pretending to be bots. Why would they do it? Let’s leave it for another newsletter.

The only challenge I foresee is that it’s incredibly hard to spell turquoise. I wrote it probably 50 times when drafting this newsletter, and I still struggle.